Athletes and modes of consciousness

I was watching a basketball game the other day (UNC defeating Clemson 77-55) and I was contemplating how the announcers would often remark on a player's focus when shooting from the free throw line. It reminded me of a conversation I had with my brother regarding Tiger Woods last summer.

He mentioned how focused Woods was when approaching the tee and I said that it was quite possibly the opposite. From what I know of how the brain works--and that's definitely not my area of expertise--one of the dividing lines between talented amateur athletes and the professionals is probably how much the professionals can avoid focusing consciously on their activity.

I know that sounds stupid but hear me out. We tend to think that we control our body's movement. Sure, there's a lot of evidence that events take place that way. We want to raise an arm--and that arm goes up. Wink an eye or tap a toe--same result. That sounds pretty convincing.

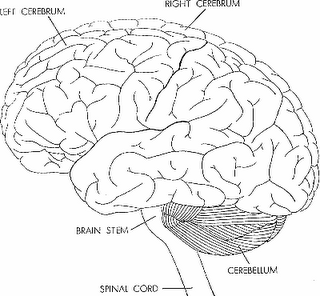

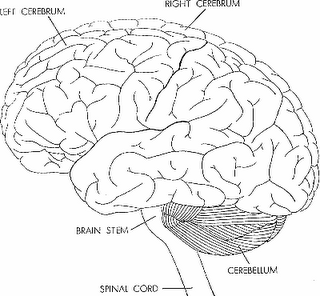

A simple version of how these things take place is that our conscious thoughts take place in the cerebral cortex (cerebrum) which is located behind our forehead. The part of the brain that controls motor (muscle) movement is the cerebellum which is located in the rear of the head, the hindbrain. The cerebrum can make demands on the cerebellum which means that you can consciously think about tapping your finger on a desk and the cerebellum causes that finger to tap. Neat.

A simple version of how these things take place is that our conscious thoughts take place in the cerebral cortex (cerebrum) which is located behind our forehead. The part of the brain that controls motor (muscle) movement is the cerebellum which is located in the rear of the head, the hindbrain. The cerebrum can make demands on the cerebellum which means that you can consciously think about tapping your finger on a desk and the cerebellum causes that finger to tap. Neat.

However while neat, it's also slow. Cerebrum to cerebellum communication is slow. This is something we're all well aware of. Consider the difference in how you move when learning a dance compared to later on when you just listen to music and move without consciously thinking about it. Or a sports analogy would be a 3rd Baseman. He'll often catch a line drive to left but not if he thinks about it. By the time he's even consciously aware it's coming at him, the ball would be over his head in left field. That's because the cerebellum can react without the intervention of the cerebrum. It's common coaching advice to "not think about it--just do it" and that's perfect advice. The cerebellum is perfectly engineered to react quickly to sense data like incoming line drives--our conscious mind is just too slow for that sorta fast reaction. So a 3rd baseman reacts to how the pitch is being delivered and the position of the bat. By the time the ball is hit, the infielder is already moving to field the ball.

The dance example is more apt for my point here though. What we often refer to as muscle memory is actually a learned response that resides in the cerebellum. We can't consciously access this information so the only way to make those smooth dance moves is to let the cerebellum and muscles do their thing and not get in the way. Similarly a professional athlete like Tiger Woods is probably doing exactly that same thing when approaching critical action. Where they look like they're focusing on what they're doing, more likely they're going into a zen-like state where they try to totally block out conscious thought and just let their cerebellum control the action. No doubt that's why many athletes want total silence when they perform complex actions.

Like a kid who yells out "Think fast" and then throws something at you, sounds distract in a way that's not immediately obvious. We process language with our conscious brain. If the words are something that requires us to take action there's a lag time while we make decisions (catch the ball) then inform our cerebellum as to what to tell the muscles. If the cerebellum has already been informed directly by the visual cortex that evasive action is needed confusion results. Two conflicting messages are being sent out and often the result is inaction. A deer in the headlights situation. In any case, hearing words will often slow down reaction time though incoherent noise has little effect.

So if you're an athlete, don't think too much. It'll slow you down. And that cartoon below--it's got it all wrong. Dinosaurs had no cerebrum. All their thinking was of the fast variety--it just wasn't conscious.

He mentioned how focused Woods was when approaching the tee and I said that it was quite possibly the opposite. From what I know of how the brain works--and that's definitely not my area of expertise--one of the dividing lines between talented amateur athletes and the professionals is probably how much the professionals can avoid focusing consciously on their activity.

I know that sounds stupid but hear me out. We tend to think that we control our body's movement. Sure, there's a lot of evidence that events take place that way. We want to raise an arm--and that arm goes up. Wink an eye or tap a toe--same result. That sounds pretty convincing.

A simple version of how these things take place is that our conscious thoughts take place in the cerebral cortex (cerebrum) which is located behind our forehead. The part of the brain that controls motor (muscle) movement is the cerebellum which is located in the rear of the head, the hindbrain. The cerebrum can make demands on the cerebellum which means that you can consciously think about tapping your finger on a desk and the cerebellum causes that finger to tap. Neat.

A simple version of how these things take place is that our conscious thoughts take place in the cerebral cortex (cerebrum) which is located behind our forehead. The part of the brain that controls motor (muscle) movement is the cerebellum which is located in the rear of the head, the hindbrain. The cerebrum can make demands on the cerebellum which means that you can consciously think about tapping your finger on a desk and the cerebellum causes that finger to tap. Neat.However while neat, it's also slow. Cerebrum to cerebellum communication is slow. This is something we're all well aware of. Consider the difference in how you move when learning a dance compared to later on when you just listen to music and move without consciously thinking about it. Or a sports analogy would be a 3rd Baseman. He'll often catch a line drive to left but not if he thinks about it. By the time he's even consciously aware it's coming at him, the ball would be over his head in left field. That's because the cerebellum can react without the intervention of the cerebrum. It's common coaching advice to "not think about it--just do it" and that's perfect advice. The cerebellum is perfectly engineered to react quickly to sense data like incoming line drives--our conscious mind is just too slow for that sorta fast reaction. So a 3rd baseman reacts to how the pitch is being delivered and the position of the bat. By the time the ball is hit, the infielder is already moving to field the ball.

The dance example is more apt for my point here though. What we often refer to as muscle memory is actually a learned response that resides in the cerebellum. We can't consciously access this information so the only way to make those smooth dance moves is to let the cerebellum and muscles do their thing and not get in the way. Similarly a professional athlete like Tiger Woods is probably doing exactly that same thing when approaching critical action. Where they look like they're focusing on what they're doing, more likely they're going into a zen-like state where they try to totally block out conscious thought and just let their cerebellum control the action. No doubt that's why many athletes want total silence when they perform complex actions.

Like a kid who yells out "Think fast" and then throws something at you, sounds distract in a way that's not immediately obvious. We process language with our conscious brain. If the words are something that requires us to take action there's a lag time while we make decisions (catch the ball) then inform our cerebellum as to what to tell the muscles. If the cerebellum has already been informed directly by the visual cortex that evasive action is needed confusion results. Two conflicting messages are being sent out and often the result is inaction. A deer in the headlights situation. In any case, hearing words will often slow down reaction time though incoherent noise has little effect.

So if you're an athlete, don't think too much. It'll slow you down. And that cartoon below--it's got it all wrong. Dinosaurs had no cerebrum. All their thinking was of the fast variety--it just wasn't conscious.

Comments

So the Nike slogan is accurate!

A good example of this is seen when Nyssa practices piano. She can start with a new Canon exercise or I guess you could call them "elaborate scales". The first time through she has to concentrate on the fingering and the notes and it's pretty slow. The second time through she has the notes and concentrates on the fingering. By the third time and onward she sits and her fingers fly up and down the keys and she may be looking at the cat sitting next to her on the bench. Her finger's muscle memory always amazed me... mine was much slower to program.

Michele sent me today; have a wonderful weekend!

Good topic, we have all done things automatically sometimes I swear I drive to work on auto pilot.

Michele didn't send me, but she's bound to sooner or later,

Mike

You know, I've had this phenomenon happen to me. Normally, I can't sink a basketball to save my life...though my odds are substantially improved if I'm not paying attention. Very weird. The brain is fascinating.

Hi from Michele's!

Here via Michele!

hi from Micheles!

I have no physiological understanding of any of this, so your explanation is now going to be memorized by a certain biology-blind journalist.

Have a good weekend!